Four Myths About Competency-Based Learning

More and more schools and learning organizations are exploring competency-based learning (CBL) as a framework for personalizing learning and prioritizing mastery. As with any complex topic, confusion and misconceptions about CBL can arise as we communicate with students, teachers, and familes about it. Developing an accurate, shared understanding of CBL is a critical first step to successful implementation.

We’ve identified four common myths associated with CBL as well as a few links to resources to help debunk them. For more resources and research, check out our Competency-Based Learning Toolkit. For an overview of what CBL should look like, read our post “What is Competency-Based Learning For?”

Myth: Competency-Based Learning is Self-Paced

CBL is personalized to the individual student, but that does not mean students learn alone and never collaborate. Think of time as a precious resource: CBL asks schools to use their articulated competencies and learning outcomes to ensure time is allocated in a way that supports mastery. Rather than always asking students to move in cohorts (by class, by grade level, by academic performance), CBL schools identify clear blocks in their calendars and weekly schedules for students to pursue individual learning targets and passions. Time for meaningful one-to-one interactions with adult guides and mentors is also routine. However, students are also collaborating in learning experiences, sharing and giving feedback on each other’s work, and participating in class activities we would recognize in any school (discussion, lecture, group work). CBL does not require schools to flip from cohort-based use of time to fully self-paced time; instead, it invites schools to design a more diverse schedule that better suits deeper learning.

Myth: Content Doesn’t Matter in Competency-Based Learning

Focusing on skills does not mean forgetting about content. Deeper learning requires fluency in relevant content and asks students to develop expertise in content areas as a way to demonstrate important competencies such as research, critical thinking, and literacy. The difference between CBL and more traditional, content-driven education models is that choices about which and how much content are driven by articulated competencies and learning outcomes. Aligning skills and content usually results in rethinking curriculum, offering students more choice, and integrating a variety of pedagogies into teaching (project-based learning, experiential learning, responsive curriculum, etc.). Most importantly, when it comes to curating content at a time when the amount of content in the world can feel overwhelming, educators shifting to CBL ponder the question, “Why?” Why do we expect students to absorb all the same content? Why do we ask students to learn math (and which elements of math are the most important to learn)? Why do we ask students to read literature (and which authors are the most important for students to know)? Why do we ask students to study history (and must they study certain periods/events)?

Myth: Competency-Based Learning is Less Rigorous than Traditional Education

Schools shifting to CBL rethink rigor in terms of authentic challenge and complexity of tasks, focusing on higher order skills (see Bloom’s Taxonomy) rather than focusing on students absorbing a wide breadth of content. Creating more complex, more challenging learning experiences for students to navigate will necessarily result in sacrificing content coverage for more thorough investigations of certain content. Words like “intensity,” “immersion,” and “deep engagement” are often associated with rigorous CBL experiences. CBL educators often think of learning experiences in terms of case studies, research projects, experiential education, and performance-based assessments, while survey courses and textbook-driven curricula are less often a part of CBL.

Myth: Competency-Based Learning is a Restrictive Mode of Learning

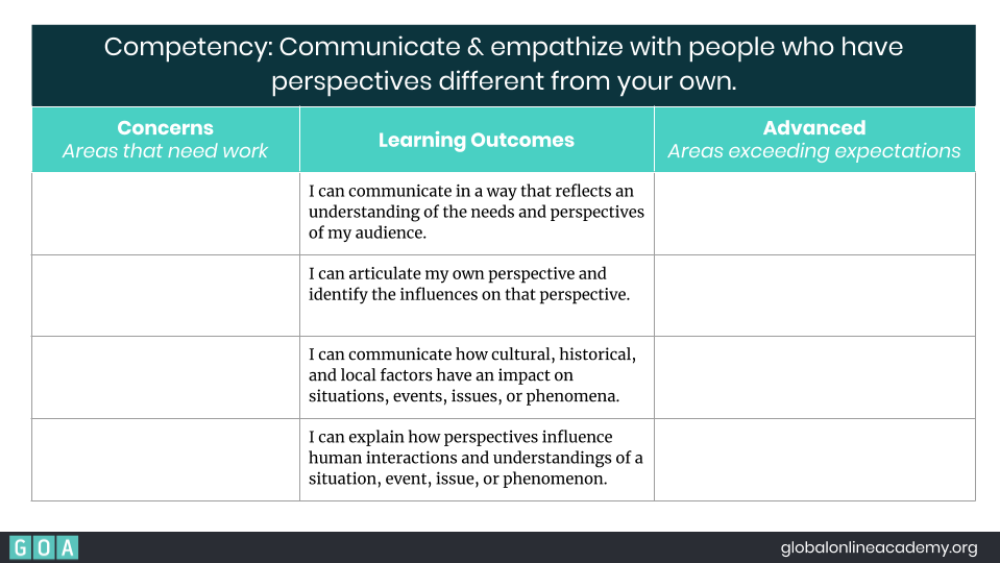

For some, CBL’s emphasis on pre-articulated competencies, learning outcomes, and rubrics might seem restrictive, limiting student creativity and educator autonomy. CBL’s emphasis on skills rather than content, however, can inspire more varied, interesting work from both students and educators. Competencies and learning outcomes offer clear parameters but leave room for educators and students to interpret what work might be done to meet those targets. In addition, use of rubric formats that de-emphasize points, such as the single-point rubric below, shows students opportunities to exceed learning outcomes. There is a floor, but no ceiling. How might the below single-point rubric invite diverse, interesting work from students and educators?

What other myths about CBL should we debunk? What are your experiences with implementing CBL? Let us know on Twitter @goalearning or email us: hello@globalonlineacademy.org

This article is adapted from the handbook in our Competency-Based Learning Toolkit.