How Might We Rethink Time to Empower Learners?

Lunch in a school cafeteria is often chaotic and quick. You dodge about foraging for food, assemble a meal, try to remember to grab silverware, and get to a table with little time to enjoy whatever you’ve gathered. It’s likely you’ll also attempt to finish your math homework or study for a Spanish quiz while wolfing down the tray of food you’ve cobbled together.

Is the school lunch a metaphor for school life? Where time constraints infringe on consumption and digestion and, of course, enjoyment?

Schools are designed to serve time. Pace, place, and space all reflect calendars and clocks and coverage. Whether the schedule of the school day or the length of a unit or the amount of homework assigned best serves students and learning is a huge question.

At Global Online Academy, however, where our student program is entirely online, calendars and clocks operate differently. Although we still wrestle with questions of coverage and the limits of a 14-week semester, the tight lines that divide class work from homework evaporate. Liberated from conventional curriculum dictators, largely time and space, we’ve seen repeatedly that transformative learning experiences can happen anywhere, at any time, if we focus on what matters most in education: an environment built on human relationships and designed for the learner.

So, to return to lunch: what makes sense if we value humanly-paced consumption that leads to healthy digestion and enduring learning — learning that leads to application and transfer of knowledge well beyond an assignment, a course, a semester, or even the entire time at school? What happens to time and pace if we make these shifts and prioritize competency and transfer?

How Rethinking Time Influences Course Design

We have 43 students in our Arabic Language Through Culture class, a mixture of first and second-year Arabic learners. Counterintuitively, placing this many students with diverse language experiences together actually enables personalized learning: by combining content, encouraging interaction among different learners, and challenging students to find their place in a rich learning community, the teachers ensure a focus on competency, not just completion.

Our two Arabic teachers have designed dozens of 20-30-minute carefully sequenced activities for language acquisition that cover a spectrum of Arabic competency. Students are guided to a pathway through teacher and self-assesment, then they advance to a more sophisticated activity when they’ve mastered foundational skills, not when the teacher says it’s time to move on.

This work requires daily practice. But, students have flexibility in how that practice is structured: 20 minutes three times a day? An hour at a time? 30 minutes before school and again after? The student controls the “when” and “how fast” of learning. Additionally, the teachers have designed “accelerated” options, so students have choices about the pace at which they pursue a concept.

Designing an online course in this way presents a time paradox: students don’t meet together every day; they move at their own pace; they practice on the schedule they determine, follow, and monitor; they progress when they show competence. Yet, if they don’t devote enough time consistently, they can’t thrive; they won’t learn the language; they won’t demonstrate competency at the junctures where it’s measured. Time is flexible yet significant. It’s akin to exercise: you choose when you work out, but you have to show up and put in the time, you have to motivate yourself, and you get tangible results from your efforts. You can also flame out, get stuck on the couch, and atrophy. Showing up matters. Taking responsibility for your own learning is fundamental.

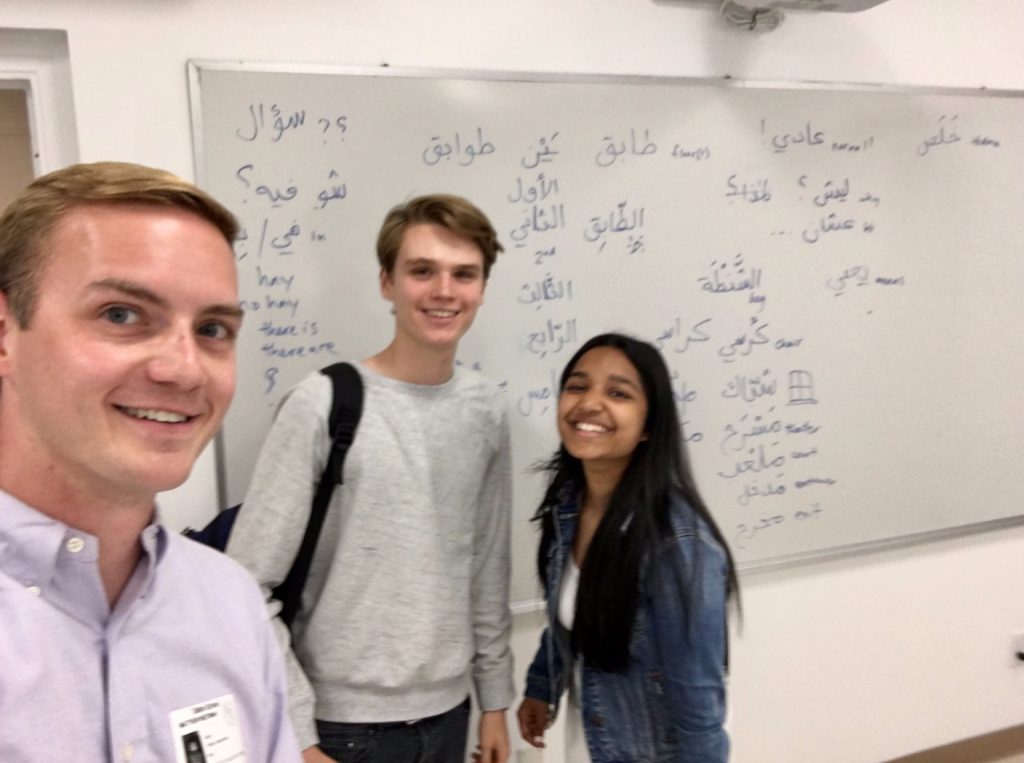

One of our Arabic teachers, Matt Westman of King’s Academy, had a chance to meet two of his GOA students at The Dalton School in New York City.

How Rethinking Time Influences Relationships and Communication

Even — or, especially — in a flexible learning environment, a healthy and multifaceted support network with ample feedback is essential. Allowing students to move at their own pace requires consistent facilitation and communication, yet the teacher will almost never have a stack of 43 tests to grade at one time. It becomes far more about daily check-in’s than marathon grading sessions.

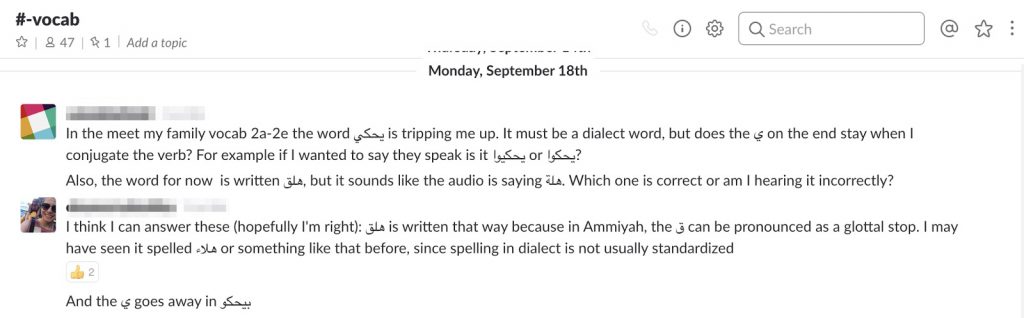

What’s also crucial: a focus on helping students develop agency, responsibility, and problem solving skills. For example, our Arabic class uses Slack, a messaging app, where they can show up at any time and ask questions, which students and the teacher answer.

Here one student poses a question, another student answers it, then one of the teachers and the original student use the thumbs-up emoji to confirm and recognize the reply.

Beyond such pragmatic uses, Slack is a social space, a place to share links to favorite Arabic music, meals, places, and people. It’s a place to share photos from students’ lives. The class becomes a close-knit community, built through Slack exchanges and collaborative assignments, especially those in the culture part of the class, which takes place in English and enables more sophisticated conversations about everything from music to fashion and politics in the Arabic-speaking world. Establishing these kinds of personal relationships enables students to become empowered learners and communicators, often not waiting for their teacher for the opportunity to practice.

Using Technology to Rethink Time: Asynchronous and Synchronous Video

The versatility of video suits the versatility of this personalized learning environment. Videos can be made or watched when it’s convenient, and they can be stopped and started and watched multiple times or re-shot and edited. Further, video enables self-assessment when students study themselves in video and analyze what they know (or don’t). In addition, the teachers have created a collection of videos that feature many Arabic speakers, so students hear variety in accents and voices, beyond those in the class.

Synchronous video calls with teachers and peers allow for real-time conversation and assessment. That is, after all, the goal of language learning: to develop the fluency needed to interact confidently in real time.

Feasting on Learning… and Food

Let’s return to school lunches, thoughtful consumption, and healthy digestion. What we feed students in schools is an ongoing topic of discussion. There are even extraordinary efforts such as The Edible Schoolyard Project and the school featured in the documentary Forks over Knives, where they’ve radically changed the food, by moving to a plant-based diet, and have seen marked behavior improvements. Many schools have committed to healthy lunches; however, have they committed to providing enough time to eat? Let’s rethink broadly how we use time in our schools. Put competency first. And, how about finding time to gather for lunch and engage around what we’re learning and discovering?

Global Online Academy (GOA) reimagines learning to empower students and teachers to thrive in a globally networked society. Professional learning opportunities are open to any educator. To sign up or to learn more, see our Professional Learning Opportunities for Educators or email hello@GlobalOnlineAcademy.org with the subject title “Professional Learning.” Follow us on Twitter @GOALearning. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter here.