Is It a Crisis or a Boring Change? Lessons on Leading Change at Schools

One evening during this past school year, I was taking my dog for a walk, listening to music, and decompressing from a challenging day at work. The shifts in approaches to instruction and assessment I was leading at my school had been met with frustration and confusion by some members of the community; I was trying to process this. During my walk, I was listening to Pavement, one of my favorite bands from my teenage years, when a line in the song “Gold Soundz” caught my attention. I hit the “back 15 seconds” button and listened again to the line:

“Is it a crisis or a boring change?”

After that line–and, to be honest, before that line too–the song doesn’t really make much coherent sense otherwise. (I’ll let you decide for yourself if a song that spells “sounds” with a “z” wants to be taken seriously.) But that question resonated with me. It’s often the dichotomous response to shifts, initiatives, and progress in education: either crisis or boring change.

One hopes that changes in education feel revolutionary and righteous–or, at the very least, timely and appropriate. One understands, however, why attempts at innovation might feel like a crisis, a threat to stability, and a risk that’s not worth it when young people’s futures are on the line. Moreover, crisis has pretty much been the default mode for the past two years of the pandemic. And while this upending has certainly provided opportunities to revisit the purpose and methods of education, we also have to empathize with students, teachers, and families who have already had a pretty rough go of it since spring of 2020.

One also understands why change might come across as boring. I was a classroom teacher for twenty years before I went into administration–and I certainly remember the cynicism that new initiatives inspired in me (and my fellow weary and battle-scarred colleagues) every few years. “This is just the latest trend,” the seasoned veterans would think, “I’ll just ride this out until it passes.” Many of these passing fads are definitely boring to the students. They couldn’t care less about differentiation, backwards design, or social-emotional learning; they want to be engaged, want a say in their learning, and want to be ready for the challenges of the world beyond high school.

So how do we respond to this false dilemma response to change? Where is the balance between defense (Don’t be afraid! This is not a crisis!) and offense (Don’t be bored! This is exciting!)?

I have perhaps passive-aggressively been using “one” and “we” to describe and explore this dichotomy–as I assume that these are universal problems–but honestly each of us is dealing with the issue on an individual or institutional level. And, during my reflective dog-walking that one evening several months ago, I was thinking about how I personally was going to respond to these tensions in my school more than I was thinking about the universality of this issue. However, what’s been helpful to me during the past year or so as we have been trying to usher in some progressive changes at my school has been connecting to others in the GOA professional learning workshops. Those of us trying to rally our fellow educators toward more learning-focused models of school are not alone.

This summer I’ve had more time to reflect on the school year (more dog walks, more musical inspiration): specifically what’s gone well and what I would’ve (or we should’ve) done differently. In the spirit of giving back, paying it forward, I want to share some of the things I’ve learned and continue to learn. And, though this has certainly been a team effort at my school, out of respect and deference for my colleagues, I’ll use the personal singular pronoun “I” moving forward as the mistakes and learning opportunities I’m sharing are mine to own.

Make Sure Everyone Feels Safe

The absolute most important thing is that people need to feel safe. Change feels like crisis when those involved don’t feel psychologically or emotionally safe. Again, the threat to physical safety during the more frightening periods of the pandemic have already made our students, families, and teachers more susceptible to stress and anxiety about other threats.

This spring I participated in GOA’s “Building Trust in Schools” leadership cohort workshop. Each of the four sessions focused on a key component to building trust: “Provide Clarity,” “Model Vulnerability,” “Prioritize Candor,” and “Strengthen Bonds”. That first one about providing clarity is first for a reason. About two weeks or so into last year’s school year, I did a great job providing clarity about the expectations for instruction and assessment. I patted myself on the back: good job, me! But providing clarity two weeks into the school year–two weeks after teachers already had momentum building in their classes, and probably at least four weeks after teachers had already planned their curriculum, created and shared their syllabus, and gotten into the zone of their teaching–is just not enough for teachers to feel safe. And, of course, when teachers don’t feel safe, this quickly trickles down to students and then is brought home to families. Any clarity that I thought I was providing was clouded by the crisis I created in my timing.

Culture Change is Slow

When I joined my current school two years ago, I was able to provide an outsider perspective on the policies, procedures, and practices that those who’d been at the school for a long time took for granted as “the way things are done around here”. Though I was able to provide this perspective, this does not mean that it was always a welcome perspective or that it meant that I could easily change “the way things are done around here”. During the professional learning teachers engaged in, I often heard the sentiment, “Philosophically, I’m on board. But practically, I’m not sure how to make this happen.” It’s not enough, I’ve learned, to convince people that change is good. They also need to know it’s going to work in their particular context.

It was heartening to hear about this same struggle from some educators during the GOA “Ask Me Anything” focused on Competency-Based Learning this past February. During this online forum, Amy Choi from Mount Vernon School in Atlanta explained that her school had been engaged in these shifts since 2018 and that the process had been an iterative and dynamic one in which teachers’ input was sought out and considered as the shifts were slowly becoming something that had full ownership and alignment. When I showed clips of this online forum to teachers and department chairs, I could see shoulders relaxing. We had been talking about Standards-Based grading and were dipping our toes in Competency-Based Learning but as we considered the context of our school–where our students, teachers, and families were at this moment–we realized that we need to develop an approach that was right for us and that might prepare us for eventual further progress.

In my own professional feedback I sought out at the end of last year, I learned that teachers felt they didn’t have enough time to develop professionally at the pace the school seemed to be heading in. In a comment, one teacher wrote, “I believe all of the changes made to grading this year are taking us in the right direction. I also believe that the changes could have been rolled out to the school community in a more effective way. We have a wonderful opportunity ahead of us and although this year was a bit rough, we are headed in the right direction and for the right reasons. Going forward we just need to be very deliberate about how we bring all stakeholders along. Making sure everyone is informed and on-board.”

In their book The Slow Professor, Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber write about the importance of “deliberation over acceleration.” They explain, “We need time to think, and so do our students. Time for reflection and open-ended inquiry is not a luxury but is crucial to what we do.”

Everything is Connected

The thing about change is that you can’t be progressive in some ways and still expect some of the traditional methods to work as well. You can’t change the way you grade, for example, and not change the way you teach. You can’t have a student-centered approach to instruction and still retain a compliance-based approach discipline. Tyler Rablin, a regular contributor to GOA and a guy worth following on Twitter, said it best in a blog post last year:

Most of the conversations I hear around assessment center on either isolated practices ("No late penalty" or "Prioritize recent scores") or vague, generic concepts ("Use standards-based grading" or "We should be focused on mastery"). All of these elements are great, but the problem is that we too often don't have a picture of how all the pieces work together to build a cohesive system.

This was my struggle for the longest time (and in some ways still is). I would change my grade book, but I didn't change the types of assessments I used. I stopped using late penalties, but I didn't develop a different method of accountability. I viewed everything in isolation, and as such, I felt like I was floundering, juggling all of these individual plates, just hoping one of them wouldn't fall.

I’ve heard some version of the plate juggling metaphor from teachers over the past year. A huge part of the feeling of crisis has to do with thinking of change as lots of individual change rather than the full-on paradigm shift that’s needed.

Of course, no teacher will be able to see the forest for the trees without feeling safe and without the time and support to make the change. It’s all connected.

Tap Into Excitement

In the end, it’s the boredom that needs to be addressed–and the best way to do that is proactively. I’ve found myself too often putting out the threatening fires–reacting to the panic and crisis–rather than actively working to ignite the sparks of creativity and innovation. And it doesn’t so much matter how excited I am about possible changes; it’s got to come authentically from the teachers and the students themselves.

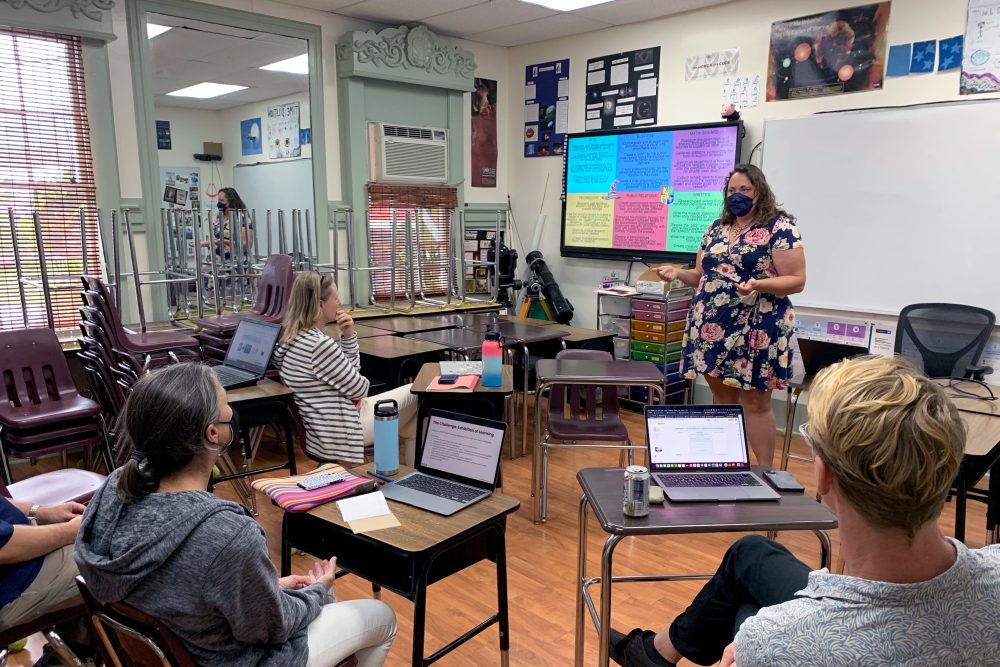

That’s where we are now as I school, I’m happy to report. Earlier in the summer, Eric Hudson, GOA’s Chief Program Officer, led some Summer Institute sessions with our teachers, and they are now jazzed about the coming school year. It’s still on me (and other leaders at the school) to stave off the crisis: providing safety, time, support, and a respect for the culture and identity of the school.

Brandon Rogers is the Assistant Head of School at Parker School on the Big Island of Hawai'i.

For more, see:

- Back-to-School Professional Learning: What Educators Need in 2022/2023

- The Power of Collective Purpose in Schools

- From Strategic Plan to Strategic Reality: The Power Middle Leaders Hold

This post is part of our Shifts in Practice series, which features educator voices from GOA’s network and seeks to share practical strategies that create shifts in educator practice. Are you an educator interested in submitting an article for potential publication on our Insights blog? If so, please read Contribute Your Voice to Share Shifts in Practice and follow the directions. We look forward to featuring your voice, insights, and ideas.

GOA serves students, teachers, and leaders and is comprised of member schools from around the world, including independent, international, charter, and public schools. Learn more about Becoming a Member. Our professional learning opportunities are open to any educator or school team. Follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter.