Six Strategies for Using Feedback to Build Community

What happens when teachers from a global network of schools get together to talk about feedback? A lot of great ideas, that’s what happens.

Last week we brought GOA teachers together for our first series of faculty meetings of the new school year. With a faculty spread across eleven time zones, the idea of a faculty meeting is different at GOA. We always have two or three opportunities for people to connect synchronously for a “fast chat” on Zoom and an ongoing “slow chat” option (on Flipgrid this semester) where faculty participate in the conversation asynchronously.

Our focus for this year at GOA is “Feedback and Transparency,” two essential components of competency-based learning, the student-driven mode of learning we’re adopting in all of our courses. Whether the chats were fast or slow, I asked our teachers the same question: How might we create community through feedback?

1. Use a protocol for low-stakes student-to-student feedback.

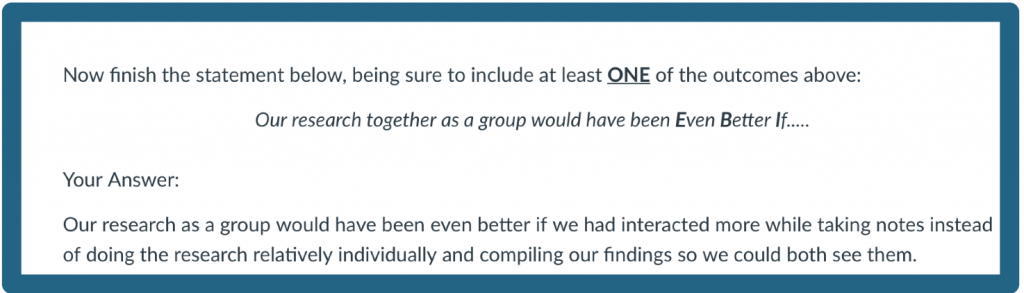

Ask students to give one another low-stakes feedback early in the course. It gets them into the habit and creates a culture of open dialogue about learning. These early peer feedback opportunities work best when highly structured. One teacher uses a framework she calls “What went well? Even better if…”

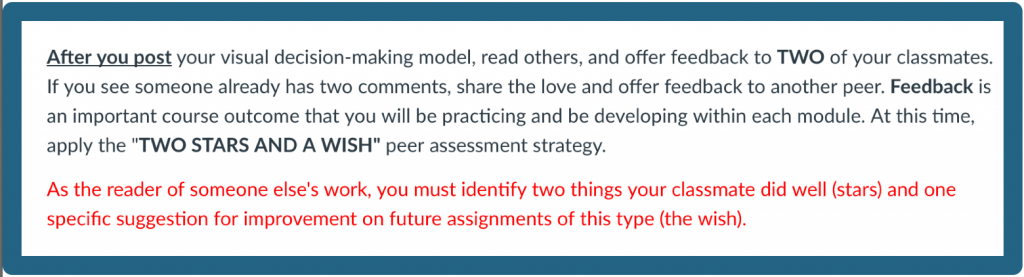

Another teacher references an activity called “Two Stars and a Wish”.

Both protocols ensure students give a compliment as well as a positively framed suggestion for improving future work. Without a strong foundation and clear expectations for what great peer feedback looks like, these exercises can descend into useless peer-to-peer flattery.

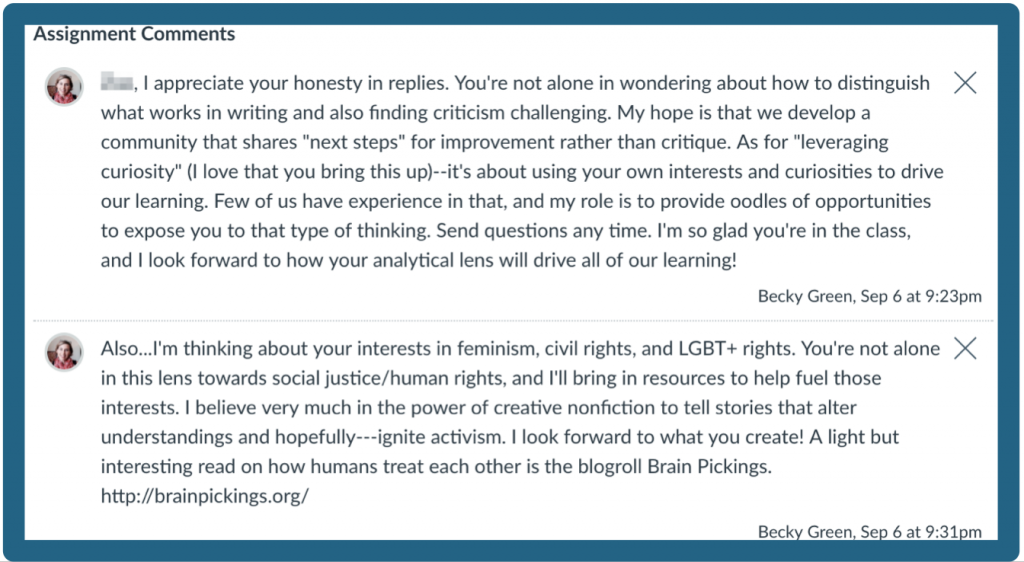

2. Lean heavily on formative feedback, lightly on grades.

Take the opportunity to give substantive, specific feedback to students a couple of times before grades are involved at all. More than a few studies show that feedback given in conjunction with grades reduce the impact of that feedback on learning and lessen students’ intrinsic motivation. The reality is that the presence of a grade compromises their ability to listen and to really hear the feedback that they most need. Early opportunities for formative feedback establish a trusting relationship with students before they feel like you are delivering a judgement. In the example below, Becky Green, GOA’s Creative Nonfiction teacher, reacts to student submissions on an assignment called “Who we are as writers, readers and learners.” The assignment is graded for completion; all students who submitted work earned 5/5 (100%) so there was no real grade judgement from the teacher. That said, Becky uses this golden feedback opportunity to build trust with the students in the first week of the course.

3. Put a face on it.

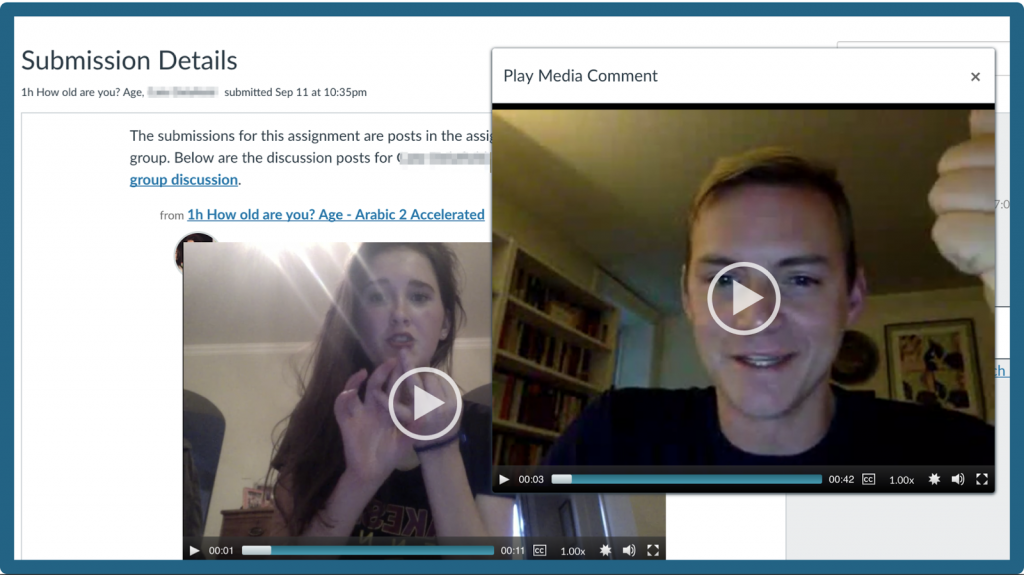

For many students, giving peer feedback can feel high-stakes. Should I be really critical? Is it better to play it safe? How can I deliver pointed criticism without hurting someone’s feelings? Many students are better equipped to negotiate these nuances of tone orally as opposed to in writing. Consider pulling students together either in person (or if you teach online, via video conference) and invite them to workshop one another’s work face-to-face. Video tools like Flipgrid lend a personal, playful feel to asynchronous feedback. Being together pulls the community together, particularly early in the course.

4. Make it personal.

Written feedback is only one piece of the puzzle. Many of our teachers opt for video feedback, at least early on, because of the warmth they’re able to communicate. Our teachers are increasingly using Loom for this. Others find that giving students formative feedback via Slack can give it the kind of conversational, personal tone that is hard to achieve in the margins of a student’s paper. It isn’t video, but it shares some of the same immediacy as a person-to-person conversation. Other teachers make a point to schedule one-on-one conferences the week after the first summative assessment, allowing them to deliver their feedback in person. In short, thinking of the different ways that a teacher’s delivery of feedback can help to develop teacher-student rapport is paramount, particularly early in the semester.

5. Give as much public feedback as possible.

Not all feedback is going to happen simply between teacher and student, or between two students. It’s important to showcase what a community of feedback looks like by delivering as much low-stakes public feedback as possible. In some cases, this happens organically as a part of a class discussion (either online or in person). Make a point to be present in the discussion, offering organic feedback in the form of questions that can push the conversation and students’ thinking to the next level, but always take care not to make yourself the protagonist of the discussion. Keep this space as student-focused as possible.

Another more structured approach to public feedback comes when the teacher synthesizes common problems she is seeing in the class’ work and points out some individuals’ excellent work to the group. In other words, deliver the criticism and the recipe for improvement to the group, and publicly praise certain individuals’ work.

6. Talk about the feedback process openly.

GOA Medical Problem Solving students will read Grant Wiggins’ “7 Keys to Effective Feedback”, and will have a follow-up videoconference discussion on the topic with a particular emphasis on the difference between advice and feedback. This is part of a broader focus on the creation of a strong community of learners and a network of students who support one another and answer one another’s questions. The plan is to be very concrete with students about what makes for great feedback and to raise the bar for student-to-student feedback across the seven sections of this course. Stay tuned: the MPS teaching team has agreed to write a follow-up post on this work and the effects that they see on peer feedback later in the course.

Many thanks to the following GOA teachers, whose ideas contributed to this post or from whose classes I pulled some of the examples above: Brandi Goodman (Lake Highland Preparatory School), Jessica Gould (American School in Japan), Jamie Spragins (Gilman School), Becky Green (Singapore American School), Kathleen Ralf (Frankfurt International School), Andrew Bendl (West Point Grey Academy), Leilani Ahina (Punahou School), David Lowen (Greenhill School), Jim Bologna (Windward School), Beth Crissy (American School in Japan), Darcy Iams (Punahou School), Laura Reysz (Park Tudor School), Fred Higgins (Cranbrook Schools), Matt Westman (King’s Academy), Frank Tempone (Latin School of Chicago).

Global Online Academy (GOA) reimagines learning to empower students and teachers to thrive in a globally networked society. Professional learning opportunities are open to any educator. To sign up or to learn more, see our Professional Learning Opportunities for Educators or email hello@GlobalOnlineAcademy.org with the subject title “Professional Learning.” Follow us on Twitter @GOALearning. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter here.