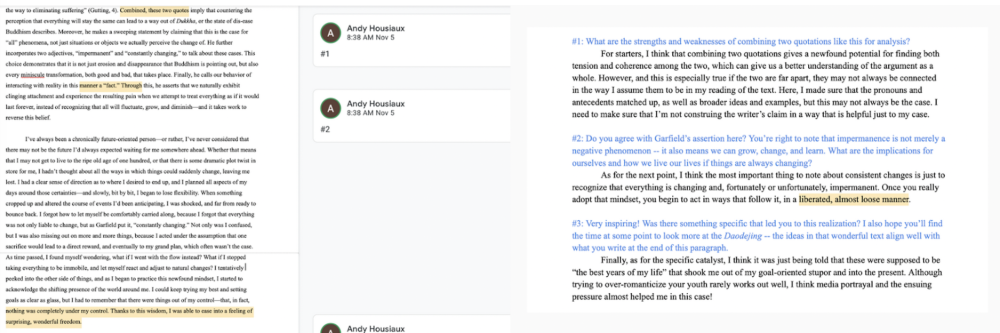

Before, During, and After: Timely Interventions for Effective Feedback

Effective feedback can powerfully enhance student learning. Yet there is often a gap between teacher practice and insights from the educational literature.

Small, research-informed shifts in our feedback practices can narrow this gap and lead to significant increases in student learning. These shifts can happen at any time: before a teacher gives feedback, during the feedback process itself, and after a student has received feedback. Feedback is best understood as “information about how we are doing in our efforts to reach a goal,” the definition Grant Wiggins offers in his influential Seven Keys to Effective Feedback.

Before: Become a Warm Demander and Differentiate Feedback from Grading

In Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, Zaretta Hammond describes the ideal of a warm demander, someone who “holds high standards and offers emotional support and instructional scaffolding [with an] explicit focus on building rapport and trust.” While there is no one single move teachers can make to become a warm demander, teachers can help establish what Hammond refers to as a “learning alliance” by making their norms and expectations clear. A meaningful approach I’ve seen with respect to feedback comes from a colleague of mine, who spends time at the start of each term differentiating clearly between grades and feedback—and why students learn much more from the latter than the former.

To do this, she brings a soccer ball to one of her first classes. Without explaining why, she asks a student to juggle it. Depending on how well they do, she gives them a grade: “B” or “72%.” Then, she asks the student to try again. This time, she gives that student focused feedback: how to position their ankle, ways to use their knees, and so on. She repeats this process with other volunteers, offering them both grades and feedback.

Then, she asks the students to reflect on the exercise: What—and when—did they learn? The students see clearly that they did not learn very much from the grade alone. By contrast, the feedback helped them understand what they were doing well and where they could improve. With further practice informed by that feedback, they could continue to learn and grow.

Armed with this deepened understanding, these students have the potential to relate differently to feedback. And because the teacher was able to demonstrate an activity that was both light-hearted and instructive, she has begun to, in Hammond’s words, “earn the right to demand effort and engagement.”

During: Focused, Future-Oriented Feedback that Inspires Further Student Reflection

In Embedded Formative Assessment, Dylan Wiliam writes that “feedback should be more work for the recipient than the donor.” As a humanities teacher who labored over student essays, I initially found these remarks puzzling—and unattainable. However, further reflection has helped me see that this ideal is not as far out of reach as I had first thought. Here are two powerful strategies for increasing student learning and engagement while simultaneously lessening a teacher’s feedback workload.

Provide Feedback in the Form of Questions

One strategy comes from Wiliam himself. He encourages teachers to ask students three questions in their feedback on an assignment. These questions should link to the learning goals of the assignment and invite further student response and reflection.

For example, in a senior elective I teach on Global Buddhisms, I asked questions about ideas from our introductory reading and an approach to textual analysis—two central goals of our course. I also added a third question that invited connections beyond the course and the reading. In response, my student followed up with further thoughts, and we used this back and forth to co-create an ongoing dialogue about their learning as opposed to a one-way monologue.

This approach also challenges me as a teacher to prioritize the ways in which I want students to learn on a particular assignment and prevents me from over-commenting on student work.

Invite Metacognitive Reflection through Self-Assessment Questions

Earlier this year, I was talking with a History teacher about his students, who often struggled with transitions between paragraphs. He dedicated a lot of his feedback to this issue, but he saw that his efforts rarely translated into lasting improvement. Instead, his students tended to make similar mistakes on subsequent assignments. He realized that while he had corrected their already-completed work, he was not prompting his students to think differently about the process of writing in a way that would impact their future work.

We discussed a small shift he could make: ask a question that inspired students to reflect on their writing. Now, instead of correcting transitions in essay after essay, he asks his students: “Which of your transitions was most effective? Why? Which was least effective? Why? How can you rewrite that transition to make it more effective?”

Questions like this inspire significant re-reading, thinking, and metacognitive reflection for students. They also require little effort from the teacher, and thus are more work for the recipient than the donor. Even more important, the intellectual work that students do in response to these questions makes subsequent transfer of understanding and improvement much more likely. As Wiliam rightly notes in The Secret of Effective Feedback, “the main purpose of feedback is to improve the student’s ability to perform tasks [they have] not yet attempted.” Metacognitive questions like the ones above prompt student thinking and learning that will improve their ability to engage with new, unseen work in the future.

After: Pause and Reflect

Students do not learn from the time and effort we put into giving them feedback. They learn from reading, reflecting on, and engaging with that feedback. Putting a grade on top of the assignment (or at the bottom, or in the LMS) can divert students’ attention away from the feedback we worked so hard to give them. Two simple strategies can help direct student attention toward our feedback: pausing and creating time for reflection.

Pause: Delay the Grade

One of the easiest ways to prevent students from reading their grade before their feedback (or ignoring the feedback once they’ve gotten their grade) is to simply withhold the grade. Teachers can delay giving students their grade on an assignment until they have read and responded to that feedback. My colleague with the soccer ball does this with all of her classes: first feedback, then reflection, then the grade. She has created an environment in which students know the feedback helps them learn, and she reinforces this idea with a pause—and dedicated time in class for students to respond to her feedback before they receive their grade.

Create Time for Reflection

The second strategy follows closely from the first one. Providing time in class for students to engage with their feedback—and, when necessary, coaching them in how to do so effectively—can significantly increase student learning. Doing so may require giving up some class time that would have otherwise gone to content, but teachers should remember Grant Wiggins’ observation that “decades of education research support the idea that by teaching less and providing more feedback, we can produce more learning.” The time we spend giving feedback only has an impact on student learning if they engage with it. Setting aside time in class for students to engage with it helps them develop this essential intellectual habit.

Concluding Thoughts: Think Small

Small shifts in our feedback practices can lead to less work and more learning, as a colleague of mine and I wrote. These shifts are evolutionary, not revolutionary: they ask for modest and achievable adjustments in our pedagogy, not a wholesale overhaul. They can be implemented at any point in the school year. We can make wise efforts before, during, or after we give feedback to students in ways that deepen their learning and make our busy lives as teachers more manageable—an especially worthy goal as we begin a new school year.

Andrew Housiaux is the Currie Family Director of the Tang Institute, where he also teaches Philosophy and Religious Studies. He is the co-author of Feedback in Practice: Research for Teachers.

For more, see:

- Stories, Strategies, Student Products: Designing for Authentic Assessment

- Four Shifts for Fostering Student Engagement

- 14 Ways Technology Supports a Culture of Feedback

This post is part of our Shifts in Practice series, which features educator voices from GOA’s network and seeks to share practical strategies that create shifts in educator practice. Are you an educator interested in submitting an article for potential publication on our Insights blog? If so, please read Contribute Your Voice to Share Shifts in Practice and follow the directions. We look forward to featuring your voice, insights, and ideas.

GOA serves students, teachers, and leaders and is comprised of member schools from around the world, including independent, international, charter, and public schools. Learn more about Becoming a Member. Our professional learning opportunities are open to any educator or school team. Follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter.