Six Key Design Elements of Successful Online Learning

For nearly a decade, GOA has been offering online courses to students. Because our classes are made up of teachers and students located around the world, we’ve focused on creating primarily asynchronous courses that are interactive, passion-based, and student-centered. How do our teachers develop high-quality online instruction that works in a mostly asynchronous online environment? Here’s the truth: just like with brick-and-mortar learning, there is no one "right" way to design online learning experiences. Many of the best GOA courses are very different from one another, but they do share some common design elements.

1. Transparent Goal-Setting

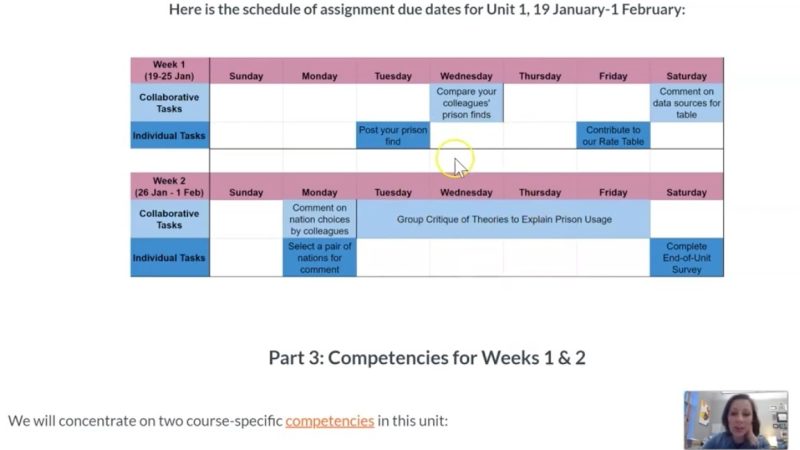

From the beginning of an online experience, be clear with the students about the goals of the unit. On module introduction pages, GOA teachers clarify which competencies and learning outcomes students will develop and how they will be assessed. Those learning outcomes populate rubrics in the unit and serve as the hooks on which teachers hang their feedback. At the end of the module, students reflect on and provide evidence of their progress toward mastery of each of those competencies, and they set some goals for the coming weeks. Whether you work in a competency-based environment or not, it’s a best practice to get clear with your students (and yourself) about the standards, competencies, unit goals, and/or essential questions that will drive your work together. Below is an example from our iOS App Design course.

GOA’s iOS App Design course and all other courses feature call-outs like this one on the first page of each module, highlighting the competencies and outcomes that will be the focus of the unit. Note the use of visual elements to support the meaning of the competency. This is from Jim Bologna’s (The Windward School) course.

Don’t underestimate how much you implicitly—rather than explicitly— emphasize and reiterate your goals for your students when you are together with them every day. To support the student-driven navigation required for online learning, lay the goals out immediately, use them to assess student work, and close your unit with a metacognitive activity where students reflect on their progress toward those goals.

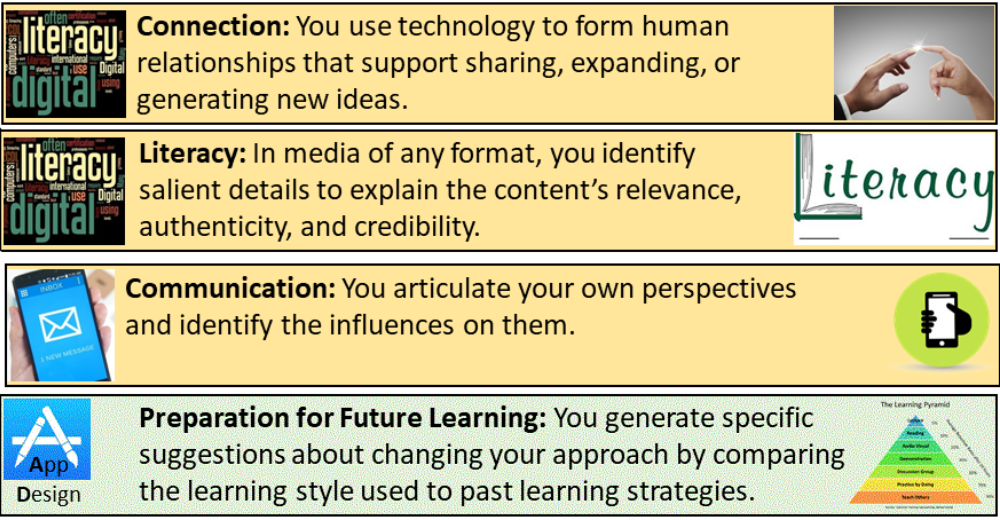

2. Proactive, Planned Communication

In brick-and-mortar classrooms, we might be accustomed to announcing assessments or other major events in advance, but online, even smaller interactions require advance planning. If students are going to connect with one another via video for small group conversations (we use Zoom), they need to form those groups and coordinate the timing of the call with their classmates (we use Doodle for this). If you want that conversation to happen before the end of the week, lay out the steps on Monday. If there is an online discussion forum that students will participate in multiple times throughout the week, be very clear about that from the beginning. It’s useful to design a system of reminders (or even better, a system in which students remind one another) to keep everyone on track. Note the way GOA teacher Kim Banion of Pembroke Hill School uses a screencast to walk her GOA students through some of these details in the module introduction video below.

Prisons and the Criminal Law, Unit 1 Walkthrough

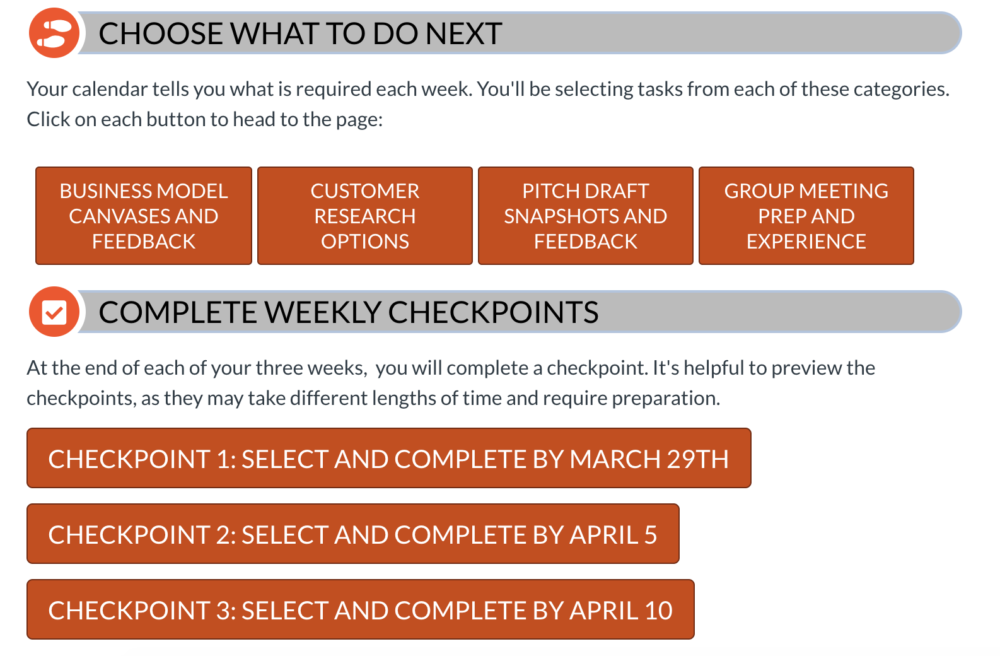

3. A Balance Between Structure and Choice

While it’s true that collaboration and discussion require advance planning in online classes, it’s also true that online learning design facilitates student choice and differentiation more readily than in-person classes. Multiple pathways and personalized pacing are more easily managed in online classes than in face-to-face settings precisely because you are not together in one room. Note the balance of structure and choice in the work that GOA Entrepreneurship teacher, Becky Green, outlines for her students below. Leveraging a simple system of links via a page in your Learning Management System (LMS) or something like a hyperdoc can change how students navigate learning. Becky's introductory video is below, followed by an image of the wayfinding system she created.

Entrepreneurship in a Global Context, Module 5 Walkthrough

In GOA’s Entrepreneurship in a Global Context class, each button here is a link that leads students to a different pathway. They choose which path to take. Online environments allow us to build these systems in advance and empower students to choose how to navigate them.

4. Elevation of Faces and Voices

Your first priority when facilitating online learning is relationships. When will students connect with one another? Will it be synchronously or asynchronously? What role will you, the teacher, play as a facilitator in each of those spaces? When will they work individually, and when will they connect with a partner or a small group?

Human interaction and ongoing conversations bring the class alive for students. Consider Becky’s module introduction video above. While she points out a variety of individual and interactive kinds of learning experiences that are planned throughout the module, she is also modeling an informal way of communicating with students via video. Video can also make for an effective, human approach to giving feedback to students. GOA Arabic teacher, Ala Hamdan, periodically uses short bites of video feedback to connect with her students in addition to or instead of written comments. Note the way she communicates personal warmth in the video below.

Arabic Language Through Culture: Video Feedback Sample

5. A Feedback Plan

Speaking of feedback, much teacher-to-student, student-to-student, and student-to-teacher feedback happens spontaneously in a face-to-face class. With facial expressions, body language, and other kinds of subtle feedback less available, the best online instructors design robust feedback ecosystems that communicate the same degree of feedback via different avenues. How and when will you give students formative and summative feedback? Will it be in a private one-on-one setting (on a rubric for a submitted assignment) or in a more public forum (like an interaction in a discussion forum)? How and when will the students give one another feedback? Our Medical Problem Solving students read Grant Wiggins’ Seven Keys to Effective Feedback and have a discussion about how to give classmates the feedback they deserve). For more on designing feedback plans, read this piece by GOA's Associate Director of Faculty Susan Fine.

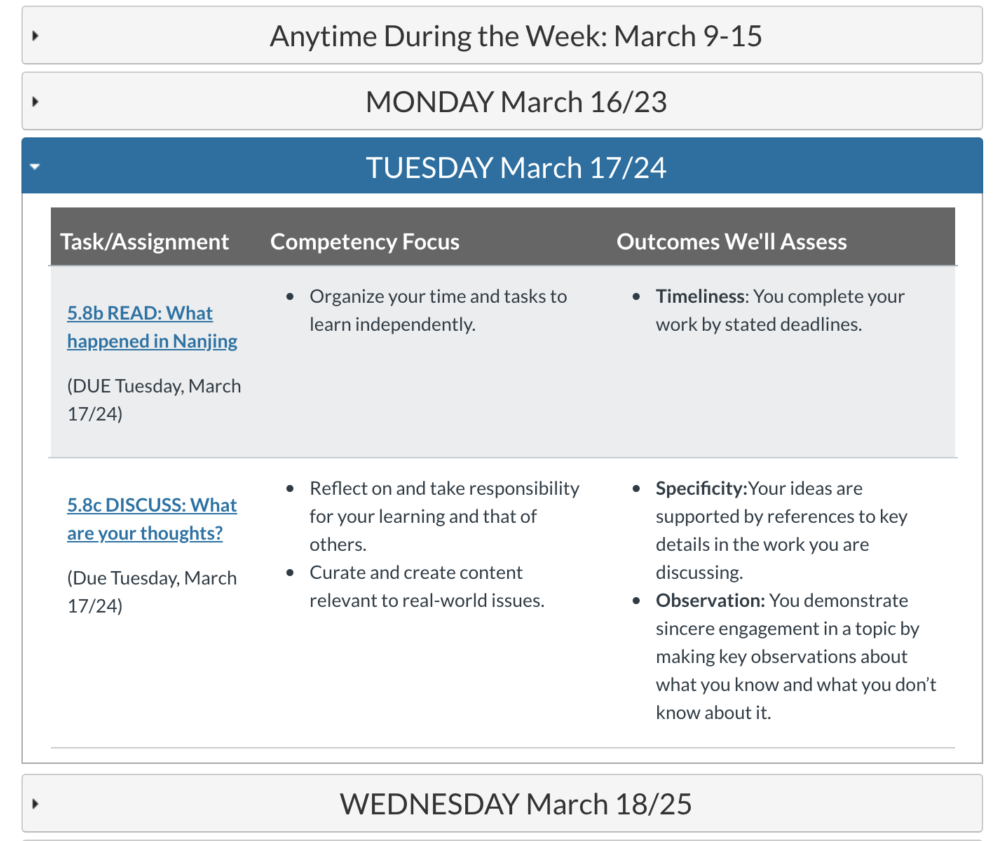

6. Student-Friendly Wayfinding

At GOA, we’ve been talking about wayfinding for some time. Director of Learning and Design Eric Hudson wrote about teaching as wayfinding for Hybrid Pedagogy in 2015, and it continues to be one of the most important and relevant elements of online learning design. The purpose of wayfinding design is to reduce the cognitive load on your students. Confusing, complicated, or overwhelming design elements prevent students from focusing on what’s important: the learning. Eric likens wayfinding in our classes to the signage and other design elements that allows us all to navigate airports effortlessly. Some basic wayfinding strategies for online learning: label assignments clearly, create video walkthroughs, use calendars and Gantt charts.

In GOA’s Genocide and Human Rights course, Kathleen Ralf of Frankfurt International School breaks out the target competencies and outcomes to be assessed by day and by learning experience. This layout is updated on the course homepage for each new unit. Also, note the systematic way she labels the assignments (5.8b, 5.8c etc.).

The primary goal of wayfinding design: keep it simple. Consider this Read-Do-Discuss framework that Megan Hayes-Golding developed as a part of GOA’s Designing for Online Learning course. This framework is clear, it is memorable, it is replicable, and it is understandable to students of different ages.

At GOA, we believe the role of the online teacher is to make important decisions about how to incorporate these design elements into their own classes and curricula. It's worth saying again: there is no one "right" way to do online learning. Just as in a brick-and-mortar environment, online learning experiences should be tailored to your students and your context.

What have you found to be the essential elements of effective online learning experiences? Let us know on Twitter. For all of our resources and offerings related to COVID-19, visit our resource page.