Use It or Lose It: Making Feedback Work for Students

Teachers spend lots of time giving their students feedback. It is one of the core components of our vocation and is arguably the primary way in which we help our students learn. And yet, the amount of time invested is not always commensurate with student learning outcomes, leaving teachers depleted and students repeating many of the same mistakes.

This is especially true in Humanities courses (which I teach), where line edits on writing and lengthy summative comments have proved stubborn in their staying power. There are many good reasons for this: detailed and specific feedback is how many teachers demonstrate that they care about their students. Alternatively, Doug Lemov notes that, because educators are experts in their field, they are particularly eager to share the wealth of resources at their fingertips. Or it could be because teachers are operating within a context in which they are using feedback to justify a grade, where copious amounts of documentation serve as an added layer of protection.

These reasons aside, it likely comes as little surprise this approach to feedback is rarely sustainable and can easily lead to teacher burnout. Moreover, it’s actually not all that effective when it comes to student learning. In order to promote long term understanding in our students, we need to move away from what I call “Feedback to Justify” and toward ”Feedback to Learn.” Daniel Willingham writes that “memory is the residue of thought,” which is another way of saying that those who do the thinking do the learning. And yet, it is so often teachers that shoulder the bulk of the thinking when it comes to feedback, leaving teachers overextended and students as passive recipients who are tasked with making sense of this information and implementing it on their own.

So let’s flip this around. Put as a question: how can we design our feedback systems such that students are actively engaging with our feedback in an effort to promote long term learning?

1. Use Video to Promote Active Engagement

I am a huge fan of using video to capture student feedback for three reasons: first, it humanizes what is often a threatening process for students. When we put feedback in writing, we are leaving students space to read tone and intent into our language (and when feedback is critical, this tone often becomes negative). Video, on the other hand, includes both facial expressions and tone of voice, which removes some of the emotional ambiguity and helps students become more receptive to what you are saying. Second, video is far more efficient on the teacher's side of things, which enables us to get feedback to students more quickly (and we know that closing the feedback gap is essential to promote learning). And third, it requires students to actively think about said feedback in an active manner. Although I use a rubric with clearly articulated standards to assess student work, I use a screencast program (like Loom) to share areas of strength and growth. I then ask students to watch the video before requiring them - and this is the critical step - to summarize my feedback in writing. This way, students have to actively think about feedback as they translate it into their own words.

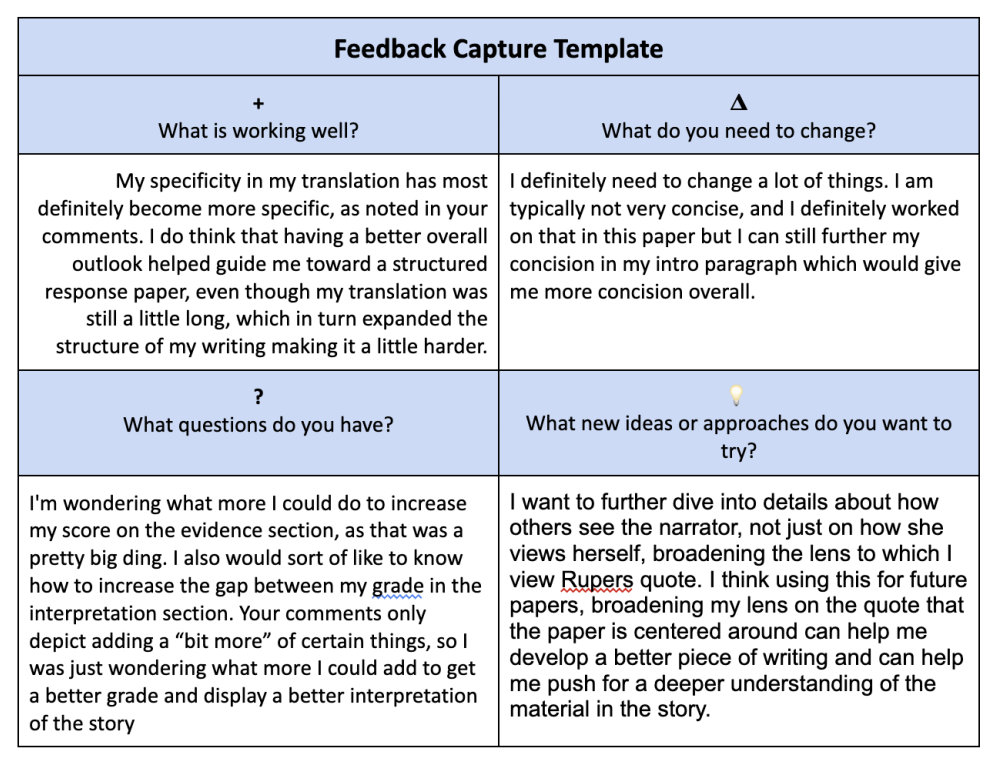

2. Deploy Feedback Capture Grids to Make Feedback Actionable

If you prefer to share feedback in writing, Feedback Capture Grids are an effective mechanism to help students make active use of your feedback, whether it be for an individual assignment or for a collection of student work over time. In this case, I share this template with students and ask them to sort my feedback into the relevant quadrant. The first quadrant (+) is for things that are working well, i.e., what students should keep doing, while the second quadrant (Δ) is for areas that need to change, or areas for improvement. The bottom row requires a bit more translation on the student end: the bottom right corner is for queries about either the feedback itself or about how to respond to specific feedback. As students complete this organizer, I scan for questions and try to clarify misunderstandings or connect to them with specific strategies (this is super easy to do if using Google docs!). The final quadrant is for new ideas, where students are asked to get specific about what they want to try next. For some students, this is particularly challenging, so I have taken to providing students a pre-populated list of common challenges in English that are linked to actionable solutions that they can try for themselves.

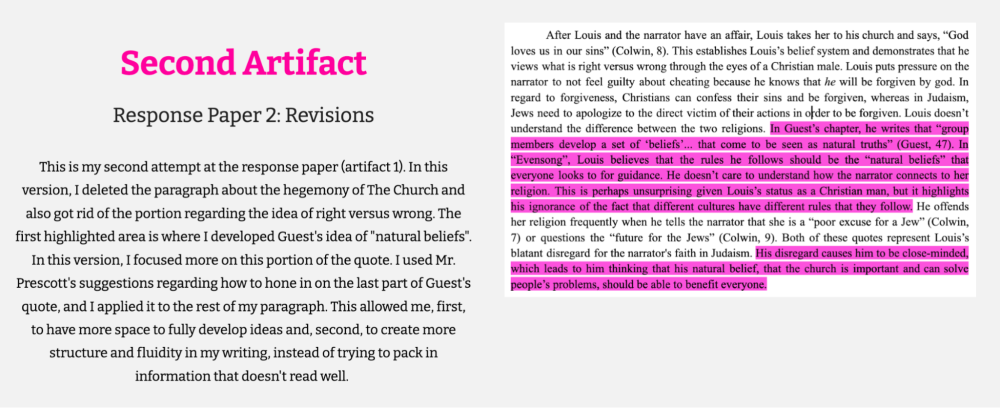

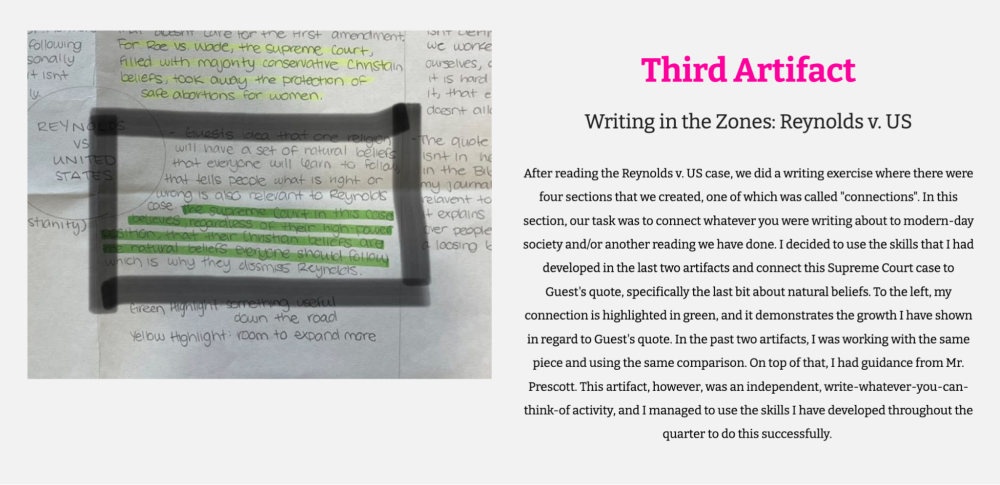

3. Use Learning Portfolios to Narrativize Engagement

Some of the best conversations about feedback occur while students work to compile a learning portfolio. Indeed, few processes give students as much ownership over their own learning as this assignment, where students are tasked with identifying an emerging thread in their own understanding and then pointing to their own work as evidence of growth. Specifically, I encourage students to include artifacts that are not just exemplary of their work but also add past work where they weren’t able to meet the standards. The goal is to show the journey of how they arrived at their current understanding, which includes past oversights, mistakes, misunderstandings, and - you guessed it - their use of feedback.

In the examples below, a student chose to focus on the ways in which they were using a theoretical framework with increasing levels of specificity. In addition to self-identifying their own emerging skill, the student clearly cites engagement with teacher feedback in the artifact analysis as evidence in their learning process.

Effective feedback doesn’t need to take huge amounts of time. If anything, it’s the opposite. What it does require, though, is for teachers to shift the onus of thinking onto students. The more we do this, the more likely it is that the residue of said thought will turn into something more enduring.

Kurt Prescott is a Humanities Teacher at Maret School in Washington, D.C

For more, see:

- Stories, Strategies, Student Products: Designing for Authentic Assessment

- Four Shifts for Fostering Student Engagement

- 14 Ways Technology Supports a Culture of Feedback

This post is part of our Shifts in Practice series, which features educator voices from GOA’s network and seeks to share practical strategies that create shifts in educator practice. Are you an educator interested in submitting an article for potential publication on our Insights blog? If so, please read Contribute Your Voice to Share Shifts in Practice and follow the directions. We look forward to featuring your voice, insights, and ideas.

GOA serves students, teachers, and leaders and is comprised of member schools from around the world, including independent, international, charter, and public schools. Learn more about Becoming a Member. Our professional learning opportunities are open to any educator or school team. Follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter.